Brought to you by

Norwich Pagan Sphere

|

Brought to you by

|

The Phoenix is a symbol important in the modern history of Greece. The newly independent state emerged from Ottoman rule in 1828, following a seven-year war of independence, with a new currency, the Phoenix. This was short-lived, however, being replaced by the Drachma, as used in classical Greece, in 1832. Following the First World War and the subsequent war with Turkey, a republic was declared in 1924, the Second Hellenic Republic. That was also short-lived, beset by coups, but issued new coins, including the 1930, 5 Drachmae coin illustrated here, before succombing to a restored monarchy in 1935.

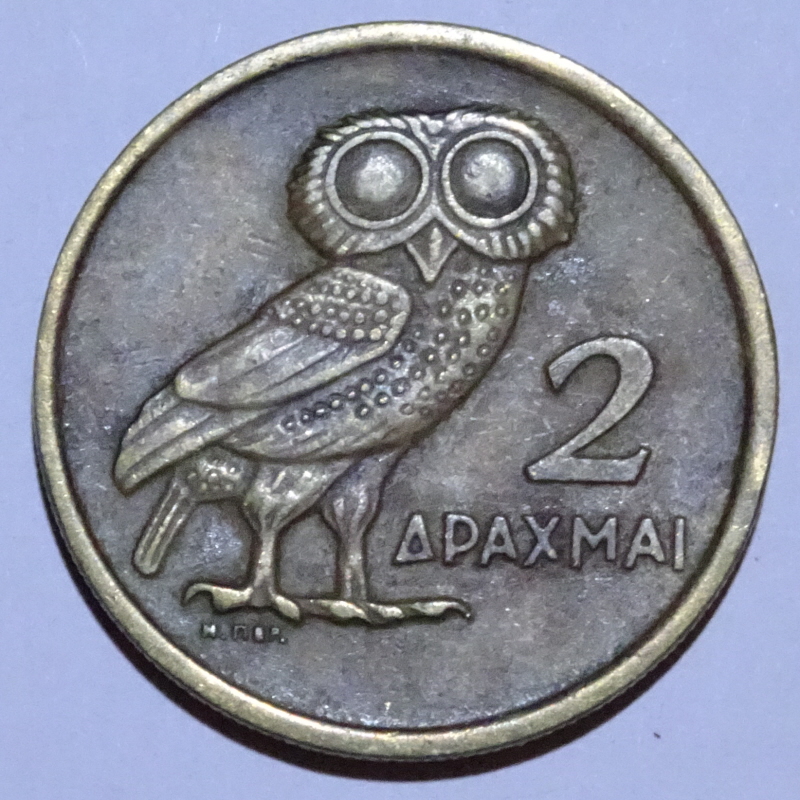

After the Second World War and the subsequent Greek Civil War, the country's politics were still turbulent. A military coup was successful in 1967, ostensibly setting out to create a republic, but a dictatorship emerged. Coins were issued, including this 1973, 2 Drachmae piece, with the traditional "Hellenic Democracy" incription, but the Third Hellenic Republic had to wait until the junta failed in 1974.

The Phoenix as a symbol of new hope from turbulent times goes back to the Roman Empire, however. It was first used by the Emperor Hadrian in the early second century CE, but by the time the sons of Constantine the Great, Constans and Constantius, were fighting each other for control of the Empire in the the fourth century, it had come to signify the restoration of a glorious, eternal empire, and be acceptable to everyone, even Christians, who saw in it a symbol of Christ's resurrection. The brothers, whose fraternal affection was in the tradition of Romulus and Remus, both claimed on their coinage that "good times are here again" ("fel temp reparatio") and Constans' coin, shown here, was issued on the 1100th anniversary of the legendary foundation of the City of Rome in 753 BCE.

The Phoenix destroyed in fire, and then emerging reborn like the Sun on a new day, may have been a recent invention at that time. It was first-century-CE Roman writers who made the Phoenix' funeral pyre regeneration a solid part of the story. However, even on fourth-century coins, the Phoenix is not shown emerging from a fire as such. It stands on a mound or pile of rocks (originally twelve for the months of the year) which has been interpreted as a funeral pyre, and it has a nimbus or halo around its head and neck, because it had always been associated with the Sun and with fire. Earlier stories talk of the Phoenix regenerating from its decayed former body or carrying the corpse of its parent to the Temple of Re in Heliopolis, city of the Sun in the Greek-controlled Egypt of the Ptolemies.

The Phoenix seems to derive from more than one origin in ancient Egypt, embellished by the Greeks and even spiced with stories from India by the time it took the fully-fledged form that has been passed down from Roman literature and imagery. In Egyptian traditions, there is the Benu-bird, probably originally an extinct Arabian giant Heron (Ardea bennuides). One of the many Egyptian creation stories has the Heron as an aspect of Re, flying across the primordial waters of Nun and unleashing a cry which brings the world into existence. The first thing to emerge from the waters is the primal mound, or Benben, a pyramidal form that was emulated as the sacred capstone of pyramids and obelisks, on which the heron of Benu alighted. The mound on which Hadrian's and Constans' Phoenix often stands seems to reflect this origin.

In the Temple of Re at Heliopolis there was a sacred object, the Benben Stone, which is thought to have been a meteorite, and meteoritic iron was held in especial reverence in ancient Egypt. A periodic comet crossing the sky and a rare meteorite seen blazing overhead before crashing to Earth in a fireball, with the heavenly rock itself discovered and set up in the Temple in Heliopolis, could well bring together the various versions of the Phoenix myth.

There is another natural phenomenon that may be involved too. The Greater and Lesser Flamingoes (Phoenicopterus ruber and P. minor) breed in salt lakes in East Africa, and stories of the sight of their nests seem likely to have found their way to Egypt. Because of the heat of the sun-scorched mud, the Flamingoes build conical mounds on which to lay their eggs. Seen from a distance, through the shimmering heat haze, the fledglings would look as though they were emerging from a burning pyre.