Brought to you by

Norwich Pagan Sphere

|

Brought to you by

|

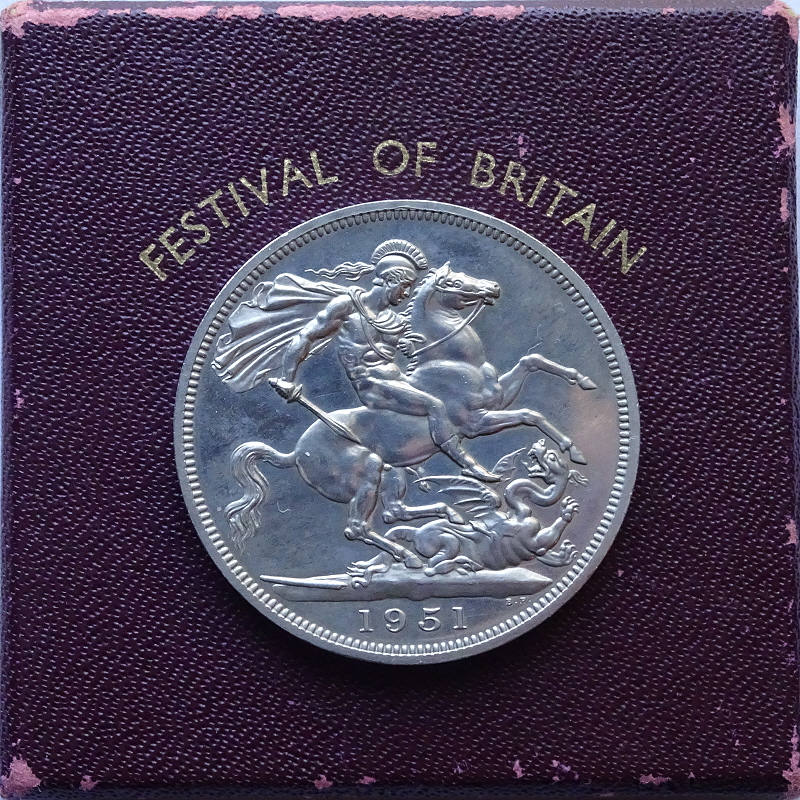

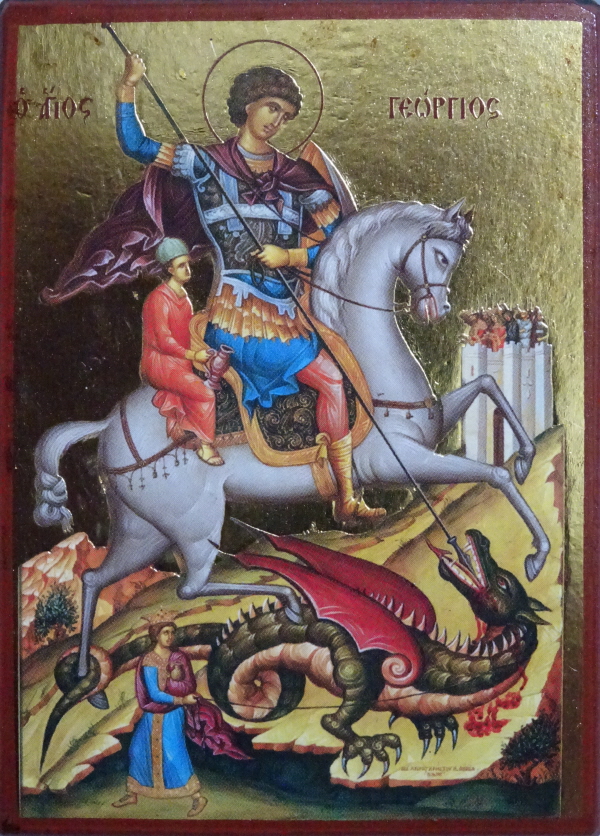

Saint George is patron saint of England - and many other places, from Moscow to Beirut! His origins are obscure and stories conflict. Did he come from Cappadocia in modern Turkey or Lydda in Palestine? Was he even a corrupt Arian Bishop of Alexandria, lynched in 361 CE? The most popular stories of his martydom take place under the Emperor Diocletion on 23rd April in either 287 or 303 CE. Surviving many tortures and performing miracles at the same time, he was finally beheaded. The famous story of Saint George and the Dragon is relatively late, appearing in the 11th century and made popular in the 13th-century Golden Legend.

In the West, the Dragon is traditionally seen as an evil force, sometimes conflated with Satan. As a result, the dragon is frequently a symbol of something to be overcome. For the temperance movement, this meant alcoholic beverages, so that Saint George would be the righteous teetotaler defeating the demon drink.

The myth of a hero slaying a Dragon goes back before Christianity, however. In Greek mythology, Apollo slays Python and Perseus rescues Andromeda from the sea-serpent, Cetus. In ancient Egypt, Set stands in the prow of the Barque of the Sun every night, deflecting the attentions of the serpent, or dragon, Apophis. In Norse mythology, Thor's nemesis is the World Serpent, Jörmungandr. But, in the legend of Jason stealing the Golden Fleece from its guardian Dragon, he does so thanks to the actions of the maiden, Medea! That tale takes place in Colchis, modern Georgia, and there dragons and serpents have traditionally been seen as more protective, with ram-headed serpent bracelets discovered by archaeologists that very much resemble those on the Gundestrup Cauldron.

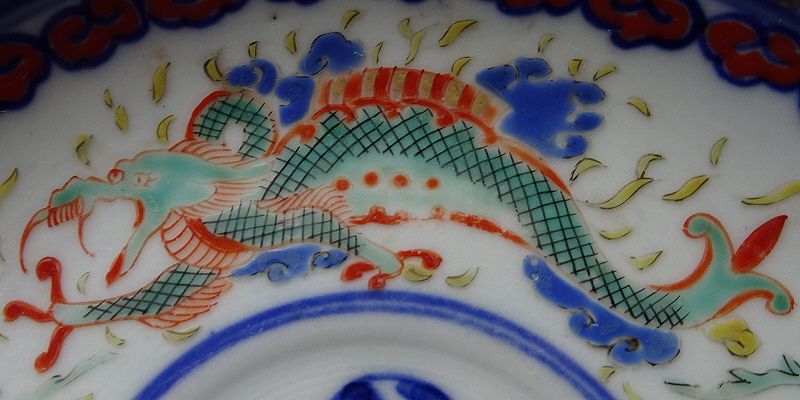

Further East again, oriental Dragons are a much more benevolent force, bringing prosperity, fertilising rain, and wisdom (in the form of a pearl). They are not slain by heroes, but dance in the streets to bring their benevolence to the people.

Whilst the Western and Eastern Dragons seem very different, they are actually very similar; it is the human response to them that varies. Dragons are an embodiment of wild, powerful forces of nature: fire, air, desert and minerals, but especially water: wild oceans, powerful rivers, and rain - they are the givers and withholders of rain. The hero - George - tames that wild nature and controls it for the benefit of agriculture and civilization. Indeed, in Central Europe, he is Green George, bringer of agricultural prosperity. In Islam he overlaps with the Green Prophet, al-Khidr, a trickster-like figure who brings wisdom and life from having drunk of the waters of immortality. It is interesting that George is not usually shown with a dead dragon (as is Saint Michael), but in the act of pinning it. He can restrict the dragon's power to allow civilization to flourish and release it when more primal energy in needed. He is also usually seen on horseback. Perhaps the horse is the Dragon tamed?

An idea that pulls everything together - indeed is like the missing piece of the jigsaw - was published by Robert Blust in 2000. His theory is that Dragons began as rainbows - the universal phenomenon caused by the polarity of rain and sun. He points out that the Rainbow Serpent is far from unique to indigenous Australian traditions and appears to develop into the various dragons seen around the world as agriculture takes hold, cities appear, and nations centralise. The rain-giving and rain-taking, divinely and mysteriously shining, gold-bringing rainbow is fought by sun gods and gods of thunder and lightning alike - Apollo, Thor, Indra... It is no accident that Thor is a god of thunder and farming! Eventually (in the West) the Dragon comes to be seen as embodying the bad forces, leaving the rainbow as a sign from God.

The city of Norwich is often called a Dragon City. The Guild of Saint George overlapped with the city corporation and had a procession every 23rd April, headed by Saints George and Margaret (also a dragon-slayer), with a tourney-style dragon, called Snap. Come the Reformation, the saints disappeared from city mayor-making processions, but the Snap remained. He still leads the Lord Mayor's Procession today.

Dragons appear elsewhere in the city too. On King Street, there is Dragon Hall, named after the dragon spandrel in its Great Hall. Three such spandrels are to be found in the Refectory at the Great Hospital on Bishopgate, as well as a bench-end carving of Saint Margaret emerging from a Dragon in the associated church of Saint Helen. Saint Margaret appears in a modern carving above the door to Saint Giles' church too. A Dragon and knight face off across the Ethelbert Gate to the Cathedral on Tombland, and a radiant mural of a red dragon (by Malca Schotten, 2016) now gazes down onto the city's shopping heart. As a more ephemeral, but long-lasting symbol, the Dragon has been the symbol of Norwich's annual Beer Festival since the early 1980s.

Norwich actually has two polar forces: the Lion and the Dragon. The Lion started as the medieval symbol of royal power in the castle, surrounded by wyverns, but the City took on the Lion, in its look-at-me mercantile pomp, with the wyverns transmuting into the Dragon that weathered the storms of religious change to come down to us as Snap and gaze down from modern murals. The controlling corporate Lion sits contentedly at the heart of the City, whilst the Dragonís wild, anarchic energy swirls around, bringing the City its prosperity and cultural vigour.

Occasionally, Norwich even has a Dragon Festival (the last one was in 2014) and the 2015 summer public art trail organised by the Break charity was Go-Go-Dragons, featuring 84 large dragon sculptures, individually decorated by artists, set out around the city.